I think I have only been on one date in my life. I was 16, he was the 19-year-old half-brother of a friend, and we saw Master and Commander and then got pizza. It all happened because he asked me. He straight up asked me. Ok we had been making out on my futon at a party, but afterward he asked if I wanted to go out sometime, and I said yes, and then we went on a date. And even though that was the only date, how fantastic is it that he could just ask and I could just go? Obviously this was not always the case because if not for an elaborate system of rules, someone might get the wrong impression.

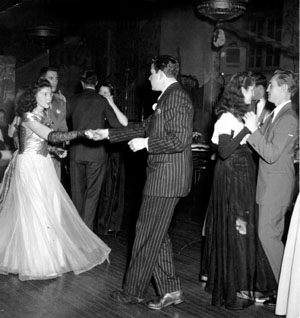

Dating as we know it did not even really exist in more western culture until the 1920s, when first-wave feminism and cars collided to pretty much invent the modern teenager. You could get a lot more necking done in the backseat of a model T than on your parent’s porch, and young people in general were rebelling against the Victorian models of etiquette and decorum solidified by their parents. Furthermore, with more women entering the workplace, the idea of what marriage meant was beginning to change. Women began looking for a friend and companion with sexual chemistry in a potential husband, not just someone to provide a house.

But we’re getting ahead of ourselves. Before the radical drunks of the ‘20s, there was courtship. You’ve probably read about it in a Jane Austen novel. A man and a woman of the same social circle are introduced formally, the man makes clear his intentions to woo this woman, and after some supervised interaction they agree to plan a wedding. Romance was not really in the picture the way we experience it today. Cassell’s Hand-Book of Etiquette (1860) states “According to the strict code of our forefathers a gentleman should ask the consent of the parents or guardians before he endeavours to win the affections of the young lady.” Because of that, “parents should be very careful whom they receive as intimate friends,” especially if they have daughters. (However, it was not just men who were in danger. Men should “beware the lady of unmeaning attentions.”)

Once a man decided he wanted to woo a lady, there were a few options. He could hang out at her house. He could hope to run into her at a ball. He could take her out with a chaperone (more on that later). He could also send her gifts of fruit and flowers, though according to Cassell, “in fashionable life, game is almost the only present that acquaintances make of each other.” For the love of god, why has nobody brought me a “Thinking of You” pheasant?

Later, if he wanted to propose, he could do so in a handwritten letter, provided he had received permission from her father first. However, Gertrude Elizabeth Campbell mentions in her 1893 book Etiquette of Good Society that “it is said in the olden times of [England], the women made the advances, and often became the suitors.” She also mentions that “In the twelfth and thirteenth centuries it seems to have been the height of gentility to hold the lady by the finger only.” In case you wanted to go retro on your next date.

Anyway, back to the more modern age of 100 years ago, when “dates” began to be a thing. How do you know when you’re ready to date? How do you ask someone on one? How do you know when it’s over. Various etiquette books over the years had advice, though some rules are unbreakable. Putnam’s 1913 Handbook of Etiquette says “is it necessary to state that a young lady who desires to hold an enviable position in smart, ceremonious society does not, whether motherless or not, go to restaurants alone with young men for any meal?” Surely it is not!

By the 1950s things had changed even more. Amy Vanderbilt says that parents know when their boy is ready to date when “his shoes will be shined to a glassy polish” and he starts paying attention to all of his ties. However, Vanderbilt offers no advice on just how this boy will ask a girl on a date, saying they “bungle through somehow in the early years of dating, eventually acquiring a certain polished technique only experience can bring.” Great. Once he does ask her on a date, it is the girl’s responsibility to signal when the night is over. To do this, “She places her napkin unfolded at the left of her plate, looks questioningly at her escort and prepares to rise. If he suggests they linger she may do so if she wishes. However, her decision must be abided by.”

Even if you were an adult with a career and your own place, some old rules still applied. Vanderbilt wrote in 1952, “A career girl, from her twenties onward, can accept such an invitation [to a single man’s house] but should not stay beyond ten or ten-thirty. An old rule and a good one is ‘Avoid the appearance of evil.’” No word on what to do with your napkin if you’re a career girl in a bachelor’s pad; we’ll get back to you on that.